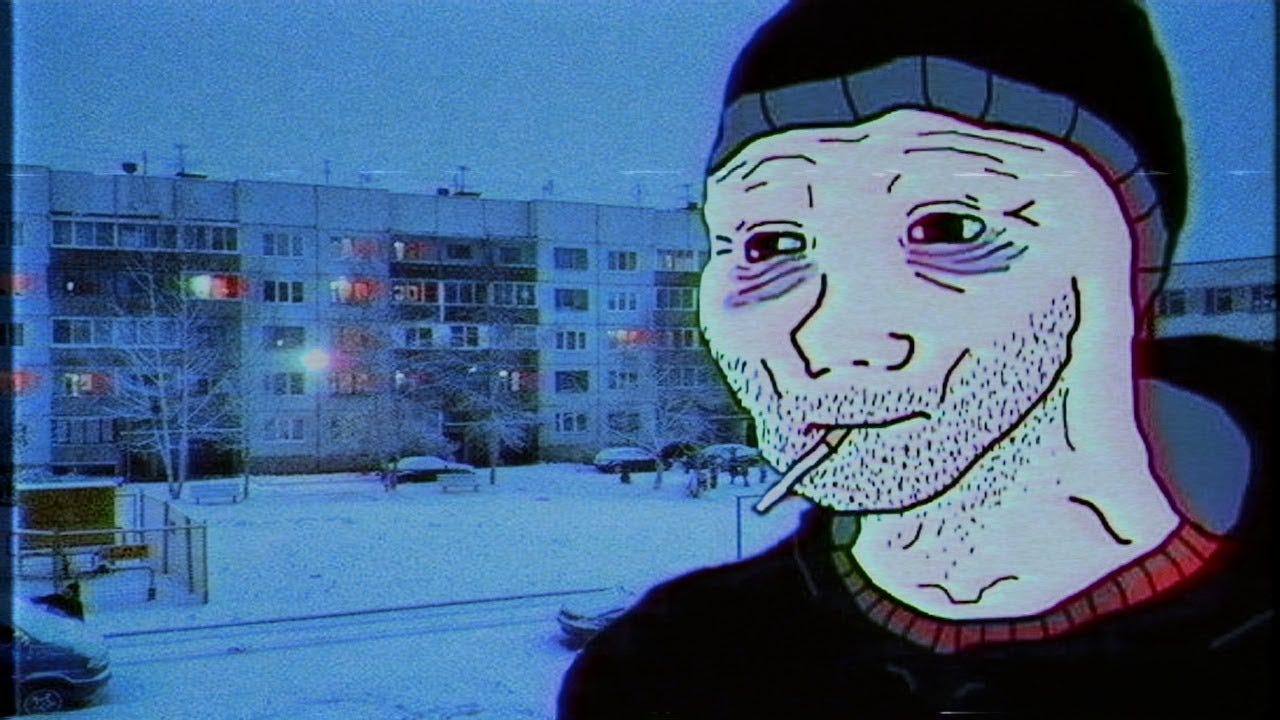

Russian doomer in his natural habitat.

There he is, all that he could hope to be — an insignificant dot of black clothing making its way around rows of equally insignificant buildings. Wading through piles of gray snow while smoking a cigarette melancholically, he sees a playground, a remnant of lost youth that leads nowhere. A spitting image of the Russian тоска (toska) — ennui, depression, hopelessness —, he is the doomer. But how exactly did he and his trademark insignificance come about?

The most direct and easily digested answer is that the doomer came about immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the veil finally lifted that there was no saving the Soviet state, what it stood for, and the industrialization that failed to deliver the happiness it promised to. While this is mostly true, ‘doomerism’ can be traced back to when the Soviet Union still existed and traces of disillusionment began to appear in Soviet media. Albeit mostly a response to хрущёвка (khrushchevka) culture, the doomer aesthetic inverts and reappropriates the motifs present in socialist realism as an artistic movement.

I. What is a doomer?

To fully understand what constitutes the doomer aesthetic, it is worthwhile to look at album covers of some stereotypically “doomer” music. Take, for example, this cover of post-punk band Angliya:

It is uncanny how much this man resembles the original ‘Russia doomer’ wojak, with them even looking in the same direction. The color scheme is a depressing blue in both pictures; the men are smoking with sad expressions, and sunlight is nowhere to be seen.

Another exhibit of the doomer aesthetic as it appears in album covers, and a much more popular one, is Molchat Doma’s album Etazhi:

This album cover focuses more on the industry side of doomerism. When any white building appears amid a sea of blue, it is a direct callback to Soviet countries’ rows of identical buildings, brought on by industrial developments in the Khrushchev era of the USSR. The cars communicate a similar sentiment: a development gone wrong.

The musical elements of post-punk make it the perfect vehicle to convey the despondent motifs of doomerism. The drum patterns are typically very unchanging — as if running from a drum machine –, there are zero guitar solos, and synths make reference to the industrial wasteland that is the doomer habitat. The singing is usually calm and the vocalist’s tone is very measured; no matter how depressing his circumstances, he sees no purpose in raging against them. Overall, there is a profound monotonous and even despondent energy to post-punk as it is utilized in doomer music such as Molchat Doma and Angliya: a specific kind of post-industrialized reality where everything looks the same all the time, and there is no point to hope for much better.

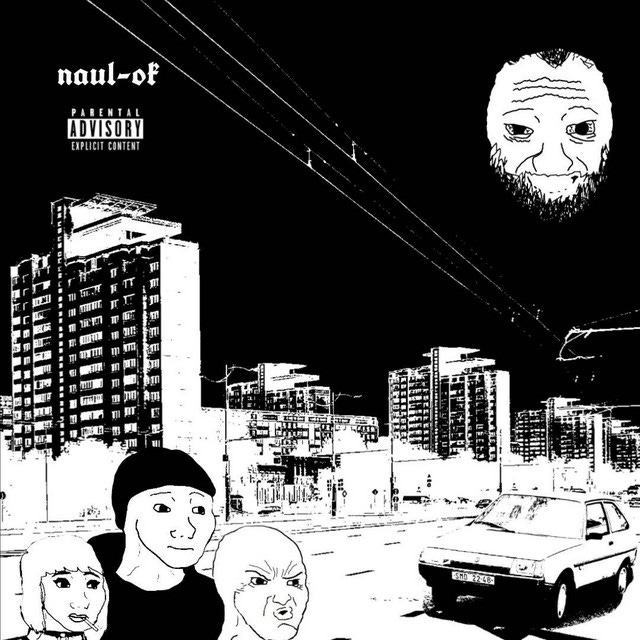

There is one non-post-punk band that is very worthy of being discussed at this point: пацюк (Pacyuk), the Ukrainian noise/nu-metal band that brought hit song “Acid Cigarette” to life. As a Reddit reply perfectly describes the song, which features lyrics about drugs, suicide, and, of course, cigarettes: “It’s some kind of suicidal sobbing”. The album cover of Pacyuk’s Ьеье is perhaps the most interesting and even self-aware cover we will be investigating:

Without the doomerjaks, this would be a normal doomer-style album cover. The identical, tall buildings, the night, and the car are all perfectly aligned with the imagery of other doomer covers. However, adding doomerjaks to this cover adds a layer of self-awareness and irony: look how the hopeless man laughs at his own hopelessness! The wojaks clearly declare the flavor of despondency that the album is supposed to communicate, and the group’s belief that there is no use in reframing the doomer outlook. Pacyuk has thus reached the final stage of doomerism: complete acceptance of the doom.

II. Post-Soviet doomerism

One of the most compelling exhibits of post-Soviet doomerism is the works of filmmaker Aleksei Balabanov. He is known as a filmmaker who consistently produces films of “beznadyoga”: a colloquial term for hopelessness. He is known as one of the first true “doomers”, with his filmography even being featured in doomer Tiktoks to Molchat Doma songs such as the one below:

Many of his popular movies — Cargo 200, Dead Man’s Bluff, and Brother — take place in either the nineties or eighties. The fall of the Soviet Union plays an important part in the circumstances surrounding each film, whether in substance or atmosphere. For instance, in both Dead Man’s Bluff and Brother, it is important to the context that they are set essentially in a lawless society. Balabanov wanted to convey how the fall of the Soviet Union led to a power vacuum, and it was an any-means-necessary race to fill that vacuum up. This led to massive rates of crime that enabled Balabanov to pump out Pulp Fiction-style films about gangs and murder while also staying realistic to the setting. Constant death, constant gunshots, constant smoking — these are the lifeblood of a Balabanov film.

The color grading of the average Balabanov film — say, Brother, as below — is grim and dark, and each movie tends to feature some sort of urban setting. There is even a scene in Brother that features the main character walking around the city and smoking alone while Nautilus Pompilius — a famous post-punk band — plays in the background. This 1997 movie is the epitome of doomer, encapsulating the brand of industrial hopelessness that doomerism is now known for.

Stills from Brother, 1997.

Even Balabanov movies set during the USSR such as Cargo 200 represent a more post-Soviet angle of doomerism, as they look back from the lens of the future, proclaiming — it was doomed from the start! However, the origins of the doomer are not so simple. Balabanov did not single-handedly create the entire aesthetic philosophy, of course — doomerism began to brew as the USSR was still standing, and all hope of a bright Soviet future was abandoned.

Stills from Dead Man’s Bluff and Cargo 200.

III. Soviet disillusionment

The Soviet predecessors of our modern-day doomerism relied primarily on criticisms of khrushchevka culture to communicate feelings of insignificance and doom. However, such criticisms constantly had to pick between being veiled or forbidden. For example, take the comedy series The Irony of Fate. In its opening, a cartoon architect is drafting an elaborate building that, over the course of several minutes, metamorphoses into a plain brezhnevka (a taller, updated version of the khrushchevka). Then, there are several minutes worth of shots of legged cartoon brezhnevki trampling beaches, deserts, and other landscapes. After that, a narrator lightheartedly states that the time of such panel buildings is a great improvement over elaborate, unique buildings, for architects no longer must overwork their brains to design buildings! This kind of criticism is very veiled in comedy – it had to have been, as the series was published in 1976.

The most doomer aspect of the series intro is the segment immediately following the legged brezhnevki — a several-minute-long series of videos of rows and rows of buildings. As the intro credits play, snow blows in and out of frame, and melancholic guitar music plays.

Still from The Irony of Fate.

The Irony of Fate was certainly not, well, doom-ful enough to be granted the full doomer treatment, but rest assured, these media got considerably more dire and hopeless after the fall of the Soviet Union — the final stage of disillusionment. To explore this progression, it is useful to compare earlier and later lyrics of the Siberian punk group Grazhdanskaya Oborona. During the Soviet Union, while the group was extremely critical of the regime (even once performing under the group name Adolf Hitler), there persevered in some of their lyrics a sliver of hope for a better world. Take the most explicit exhibit of such hope, the 1987 song “We are — ice”. In the song, vocalist Egor Letov repeatedly chants, “We are the ice under the mayor’s feet, we are the ice under the mayor’s feet, we are — ice!” to show the value of collective resistance — if there is enough resistance, the oppressive mayor will fall eventually.

However, that hope does not continue onward towards the tail end of Grazhdanskaya Oborona’s discography, which instead features songs such as the 2005 “So-so pirozhok”. In the song, the line “only one thing in my pocket, a so-so pirozhok; every one of us is a so-so pirozhok” seems to represent how the people of Russia, and other post-Soviet countries, feel as though they are treated like rows of identical possessions, buildings, objects, and the like. Repeating “every one of us is a so-so pirozhok”, Grazhdanskaya Oborona supplies a grim contrast to “We are — ice”: instead of repeating a mantra of hope and change, the band is repeating one of dire staticity, one emblematic of rows of identical and insignificant humans.

Grazhdanskaya Oborona’s lyrical evolution shows that there not only wasn’t but also couldn’t have been a true doomerism in a non-post-Soviet setting. People hoped for a better future as the Soviet Union collapsed, but were not met with such a future at all, but rather a lawless one.

IV. Socialist realism

The doomer aesthetic is, essentially, an inversion of socialist realist art, in the sense that it uses the same motifs to convey an opposite message. Of these motifs, it is mainly industry, youth, and health that are most relevant, as well as general color schemes and artistic choices.

Take, for example, the 1962 painting Wedding in a Tomorrow’s Street:

Yuri Pimenov, Wedding In a Tomorrow’s Street, 1962.

The khrushchevki are visible, alongside cranes, tubes, and countless planks of wood. The sky is a light, sunny blue. The people are surrounded by the same industry as seen in doomer imagery, but it is now being shown in a very positive light. Instead of hopelessness, there is hope — there is a tomorrow, and the rows of buildings are part of it. Another painting with strong ‘buildings of tomorrow’ motifs is the 1937 painting New Moscow, also by Yuri Pimenov:

The painting looks almost exactly like a Balabanov still, just with brighter colors. Although the painting features Stalin-era architecture rather than the Khrushchev or Brezhnev-era buildings we have already thoroughly investigated, it shows the same hope for tomorrow manifested through buildings and cars.

Another such socialist realist motif is youth, symbolizing hope, reinvention, and new beginnings. We will soon see how this motif plays out in doomerism, but for now, let us examine this socialist-realist artwork:

The colors are once again very bright — even brighter than those of the previous paintings. There is lots of red in this particular painting. The sky is once again bright, and the youth is looking at Stalin and smiling. They hold drawings, toys, and models: they are satisfied and entertained. On the flip side, a common doomer aesthetic motif is the lonely playground amidst snow and panel buildings, like so:

In these pictures, the images of youth and industry depicted so positively in socialist realism are turned upside down. There is no tomorrow’s street, only yesterday’s.

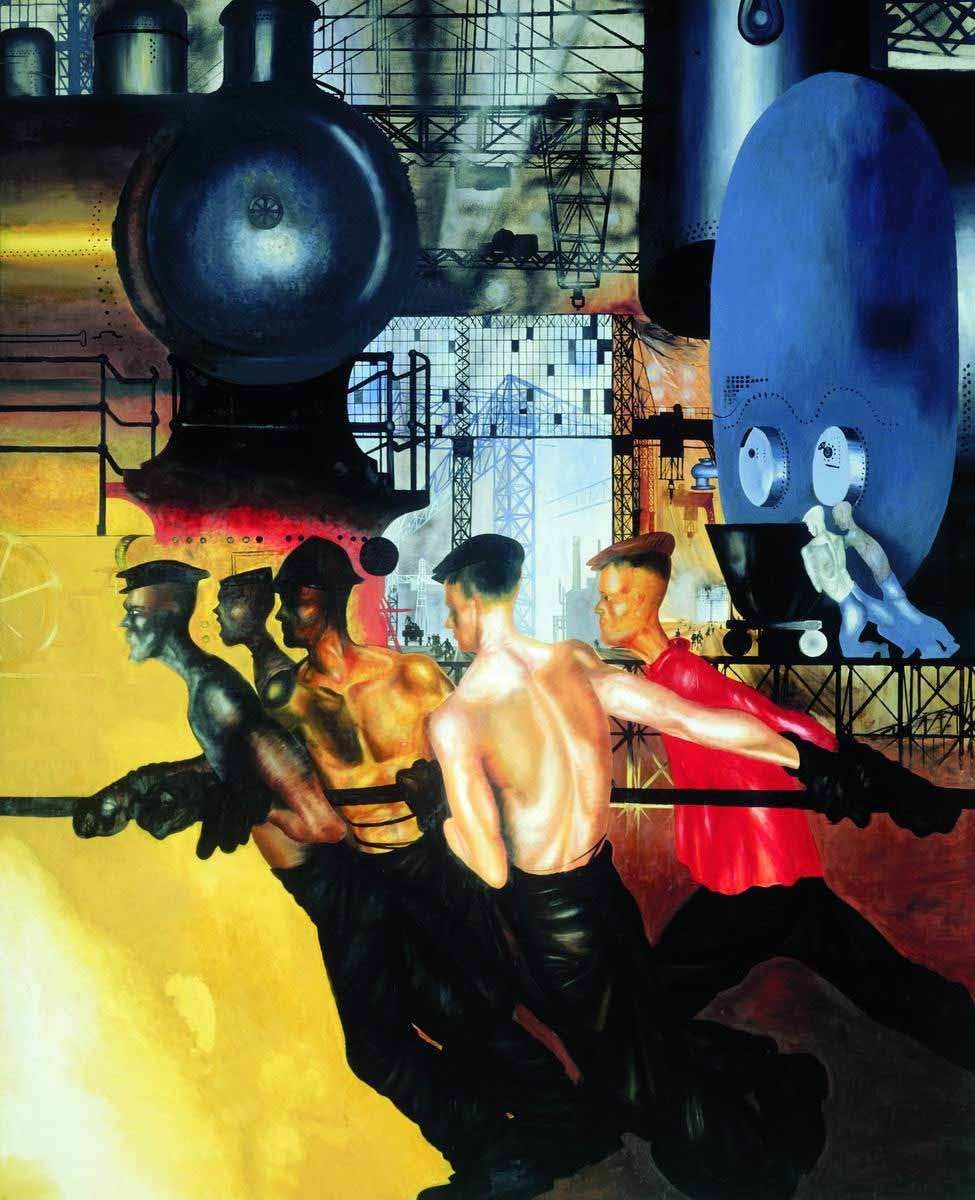

The idealization of the worker in socialist-realist art led, thus, to an ideal masculinity, in contrast to which the doomer represents one who has failed at a traditional masculine role. To explore this, let us examine yet another Pimenov painting — the 1927 Increase the Productivity of Labor — in which buff, bare-chested men work alongside a sea of flames with an emotionless expression:

These men are healthy, strong, productive — in essence, the ideal males. So are the men from the famous socialist realist painting Young Steel Workers, painted four decades later:

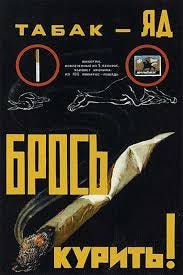

Now, take another look at the lonesome doomer. He has eyebags, wrinkles, and stubble. It is apparent from the first gaze upon his sad eyes that he does not take care of himself in the slightest. Turn your attention, now, to the cigarette he perpetually dons in his mouth: the prime marker, or even declaration, of unhealthiness. As evident due to the completely contrasting depictions of health and wellbeing, doomer and worker inherently exist on opposite sides of a dichotomy. The worker’s health declares him a successful male; the doomer’s lack thereof, a failed one. There is a reason, after all, that USSR posters so often pushed for health measures such as quitting smoking, as the one below does:

Tobacco — POISON. QUIT smoking!

The purpose of these comparisons is not to say, with any concrete certainty, that doomerism originated as a direct response to socialist realism as a movement, as much as a response to the general prospect of hope that socialist realism was designed to convey.

While doomerism has a very particular look, its general sentiment has influenced plenty of ‘non-doomer’ Russian media as well. Take, for one final exhibit, the song “Strashno” — Afraid — by Russian experimental post-punk group Shortparis. This is an extremely complex song that has been picked apart to shreds by Russian video essayists on YouTube, but we will only focus on one of the lyrics, which writes, “The ice will not save us, the mayor marches onward”. This is, if you recall, a direct reference to Grazhdanskaya Oborona’s “We are — ice”, and thus another Pacyuk-esque venture into the self-aware aspect of doomerism. The hope is all but explicitly stated to be gone. I am hopeless, you are hopeless, the buildings are hopeless, the country is hopeless, everyone is hopeless. Yet, everyone is equally hopeless, and there is something very distinctly beautiful in that.

2236 words

Sources

Angliya. “Warmth From Cold Hands.” 21 Feb. 2019.

Balabanov, Aleksei, director. Dead Man’s Bluff. 2005.

Balabanov, Aleksei, director. Cargo 200. 2007.

Balabanov, Alekseii, and Sergeii Selianov. Brother. Kino International, 1998.

Bevzenko, Ivan. Young Steel Workers. 1961.

FSUE Mosfilm cinema concern. “Ирония Судьбы, Или С Легким Паром, 1 Серия (Комедия, Реж. Эльдар Рязанов, 1976 г.).” YouTube, YouTube, 28 Mar. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVpmZnRIMKs&t=371s.

Grazhdanskaya Oborona. “Reaanimatsiya.” 2005.

Ignatyev, N. Tobacco -- POISON. QUIT Smoking! 1957.

Molchat Doma. “Etazhi.” 7 Sept. 2018.

Pimenov, Yuri Ivanovich. Increase the Productivity of Labor. 1927.

Pimenov, Yuri Ivanovich. New Moscow. 1937.

Pimenov, Yuri Ivanovich. Wedding in a Tomorrow’s Street. 1962.

vdmshv. TikTok, www.tiktok.com/@vdmshv/video/7050166111391862018. Accessed 8 Apr. 2024.

“Shortparis - Страшно.” YouTube, YouTube, 19 Dec. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=FUdteCBRX9c.

“Сігарета з Кислотою.” YouTube, YouTube, 1 Apr. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=LTs7c1xMVtw.

“Мы - Лёд.” YouTube, YouTube, 9 Nov. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4osVwFwOJQ.